(First published as an insert in the USA Today published on Sept 1, 2017)

(First published as an insert in the USA Today published on Sept 1, 2017)

Imagine you are a prize fighter facing the toughest opponent of your life. You step into the ring only to realize you have no boxing gloves and no corner man to coach you through the fight. You have the heart but not the necessary tools.

Now imagine your opponent is a terminal illness and what you are missing is a cure and doctors able to offer you viable treatment options. This is the harsh reality for millions of American children who have been diagnosed with a rare disease.

Finding research incentives

The National Institute of Health estimates that there are roughly 7,000 rare diseases affecting 25-30 million Americans. Only about 500 of these diseases have any sort of treatment option and rare diseases disproportionately affect children. Only 30 percent of these children will live to their fifth birthday.

In 1983 Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act. This landmark piece of legislation provided a set of incentives that encouraged the pharmaceutical industry to consider rare disease drug development as a profitable business prospect and thereby increased interest in rare diseases in the private sector. Less attention, however, has been given to the creation of public institutions that support research crucial to medical advancement in genetics, which would greatly benefit the rare disease community.

The formation of a number of departments within the National Institute of Health such as the Office of Rare Disease Research and the Office of Rare Disease Research at National Center for Advancing Translational Science are hubs of cutting-edge research that provide the essential knowledge advancements. The pharmaceutical industry then uses these advances to develop life-saving drugs for rare diseases. Rare disease treatments depend on these public-private partnerships. Without this synergy millions of children with rare diseases would be completely excluded from opportunities for medical advancement available to children with more common diseases.

Children need our help

As Americans, we operate under the assumption that society owes each child born into this world a certain set of opportunities and protections. We fund public education because all children deserve an education. We fund federal departments that prevent child exploitation because all children deserve protection. Let us continue our commitment to each child born into this country by agreeing that every child deserves a treatment option no matter how rare the disease. Let’s find 7,000 more boxing gloves because every child deserves the chance to fight.

As America’s lawmakers debate various ways to fix our broken health care system, we in the rare disease community are alarmed by proposed cuts to Medicaid funding. The term “rare disease” is a bit paradoxical. When viewed individually, a particular disease may affect a minuscule portion of the population. But when considered as a whole,

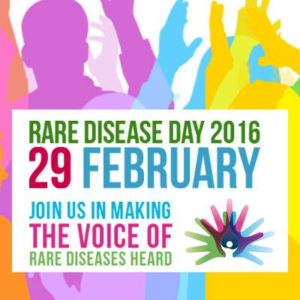

As America’s lawmakers debate various ways to fix our broken health care system, we in the rare disease community are alarmed by proposed cuts to Medicaid funding. The term “rare disease” is a bit paradoxical. When viewed individually, a particular disease may affect a minuscule portion of the population. But when considered as a whole, February 28th is internationally recognized as Rare Disease Day. My daughter, Chloe, was diagnosed with a rare and terminal disease at the age of two in a miraculously short time due to the brilliance of her neurologist. The neurologist was Canadian. Chloe’s only hope of survival was a bone marrow transplant, a risky and arduous procedure. We put our youngest child’s life in the hands of a capable and caring surgeon at the Mayo Clinic. She was Pakistani. Throughout the transplant there were long days of agony and fear as we awaited the outcome. Since her immune system was completely gone, neither she nor I could leave our tiny ICU room. The resident on the medical team brought me a Starbucks coffee each morning. He was Egyptian. When it became clear that Chloe’s chances for survival were non-existent, we met with the team to decide whether to try a risky and painful second transplant or let her go. I shared with the doctors that I believed deeply in medicine but also that, at the end of the day, my Christian faith informed me that it is God who decides how many days we have on this earth. I sensed that my decision resonated deeply with my Pakistani doctor’s faith as well. She was a Muslim.

February 28th is internationally recognized as Rare Disease Day. My daughter, Chloe, was diagnosed with a rare and terminal disease at the age of two in a miraculously short time due to the brilliance of her neurologist. The neurologist was Canadian. Chloe’s only hope of survival was a bone marrow transplant, a risky and arduous procedure. We put our youngest child’s life in the hands of a capable and caring surgeon at the Mayo Clinic. She was Pakistani. Throughout the transplant there were long days of agony and fear as we awaited the outcome. Since her immune system was completely gone, neither she nor I could leave our tiny ICU room. The resident on the medical team brought me a Starbucks coffee each morning. He was Egyptian. When it became clear that Chloe’s chances for survival were non-existent, we met with the team to decide whether to try a risky and painful second transplant or let her go. I shared with the doctors that I believed deeply in medicine but also that, at the end of the day, my Christian faith informed me that it is God who decides how many days we have on this earth. I sensed that my decision resonated deeply with my Pakistani doctor’s faith as well. She was a Muslim. Driving home from work last week it was surreal to listen to local news coverage of the live press conference in Chanhassen, MN, knowing that the whole world was tuning in to my home town. Local law enforcement was addressing the public outside of Paisley Park, home of the rock legend Prince who, of course, had just died. The grief for us Minnesotans is unique and multilayered because Prince, while being an intensely private man, was also deeply embedded in his Minneapolis community and its suburbs where he was born and raised. After the renovation of the Minneapolis fixture the Uptown Theater, a local movie critic mentioned in passing that Prince occasionally slipped in to watch a film. (It became my habit after that to scan the audience to see if he and I had the same cinematic taste.) He had his own private table at the Dakota Jazz Club downtown. Some of my friends live a few doors down from one of his rental properties. I had even heard that he would once in a while do some door to door evangelizing for his small church located in St. Louis Park just minutes from my own home.

Driving home from work last week it was surreal to listen to local news coverage of the live press conference in Chanhassen, MN, knowing that the whole world was tuning in to my home town. Local law enforcement was addressing the public outside of Paisley Park, home of the rock legend Prince who, of course, had just died. The grief for us Minnesotans is unique and multilayered because Prince, while being an intensely private man, was also deeply embedded in his Minneapolis community and its suburbs where he was born and raised. After the renovation of the Minneapolis fixture the Uptown Theater, a local movie critic mentioned in passing that Prince occasionally slipped in to watch a film. (It became my habit after that to scan the audience to see if he and I had the same cinematic taste.) He had his own private table at the Dakota Jazz Club downtown. Some of my friends live a few doors down from one of his rental properties. I had even heard that he would once in a while do some door to door evangelizing for his small church located in St. Louis Park just minutes from my own home. Before my daughter passed away from a rare disease I had never heard of “Rare Disease Day” and knew next to nothing about the impact rare disorders have on society. Over the past few years I have learned that rare diseases play a larger role in public health than most people realize and deserve consideration from the medical community, policy makers, and the general public.

Before my daughter passed away from a rare disease I had never heard of “Rare Disease Day” and knew next to nothing about the impact rare disorders have on society. Over the past few years I have learned that rare diseases play a larger role in public health than most people realize and deserve consideration from the medical community, policy makers, and the general public. This week the story of Turing Pharmaceutical CEO Martin Shkreli and his hiking of the price of a decades-old pill that treats the serious illness toxoplasmosis from $13.50 to $750 broke. I was outraged as the vast majority of Americans were. But a special wave of nausea swept over me when I read more about this former hedge-fund manager turned biotech venture capitalist. In his biography, characterized by an incessant thirst for wealth and shady business practices, is a fact of personal significance to me. In 2011, Mr. Shkreli founded biotech firm Retrophin with the goal of focusing on medicines for rare diseases.

This week the story of Turing Pharmaceutical CEO Martin Shkreli and his hiking of the price of a decades-old pill that treats the serious illness toxoplasmosis from $13.50 to $750 broke. I was outraged as the vast majority of Americans were. But a special wave of nausea swept over me when I read more about this former hedge-fund manager turned biotech venture capitalist. In his biography, characterized by an incessant thirst for wealth and shady business practices, is a fact of personal significance to me. In 2011, Mr. Shkreli founded biotech firm Retrophin with the goal of focusing on medicines for rare diseases.

Mother’s Day came and went and with it the familiar struggle to find a label for myself. I like definitions for things. Labels are comforting and secure. Call it a personality trait, but I often feel if I could just find a word that describes the person I’ve become since losing my daughter I would somehow be able to own that title and act the way a whatever-the-word-is acts. I once heard a person say that we can find titles for all kinds of loss. A woman who loses her husband is a widow. A man who loses his wife is a widower. A child who loses his or her parents is an orphan. But, so the argument went, the loss of a child is so deep and painful that humanity hasn’t been able to find a word for it. Maybe that’s true. The thought resonated with me when I first heard it. But in the years since losing Chloe, I have come to a different conclusion for why we haven’t found a special title for a person who loses a child.

Mother’s Day came and went and with it the familiar struggle to find a label for myself. I like definitions for things. Labels are comforting and secure. Call it a personality trait, but I often feel if I could just find a word that describes the person I’ve become since losing my daughter I would somehow be able to own that title and act the way a whatever-the-word-is acts. I once heard a person say that we can find titles for all kinds of loss. A woman who loses her husband is a widow. A man who loses his wife is a widower. A child who loses his or her parents is an orphan. But, so the argument went, the loss of a child is so deep and painful that humanity hasn’t been able to find a word for it. Maybe that’s true. The thought resonated with me when I first heard it. But in the years since losing Chloe, I have come to a different conclusion for why we haven’t found a special title for a person who loses a child.