As America’s lawmakers debate various ways to fix our broken health care system, we in the rare disease community are alarmed by proposed cuts to Medicaid funding. The term “rare disease” is a bit paradoxical. When viewed individually, a particular disease may affect a minuscule portion of the population. But when considered as a whole, roughly 1 in 10 Americans live with a rare disorder. For some the rare disease is progressive and eventually fatal, as in the case of those of us parents who have watched our children develop typically before the onset of a neurodegenerative disease slowly robs them of their function and eventually their lives. For others, the disorder is manageable with diet modifications, scrupulous monitoring by medical specialists, or changes to our environments that allow us to work and function in society.

As America’s lawmakers debate various ways to fix our broken health care system, we in the rare disease community are alarmed by proposed cuts to Medicaid funding. The term “rare disease” is a bit paradoxical. When viewed individually, a particular disease may affect a minuscule portion of the population. But when considered as a whole, roughly 1 in 10 Americans live with a rare disorder. For some the rare disease is progressive and eventually fatal, as in the case of those of us parents who have watched our children develop typically before the onset of a neurodegenerative disease slowly robs them of their function and eventually their lives. For others, the disorder is manageable with diet modifications, scrupulous monitoring by medical specialists, or changes to our environments that allow us to work and function in society.

Nearly all of us have lived through the frustrating experience of the “diagnostic odyssey.” The diagnostic odyssey is a term used to describe the journey through the medical system a rare disease patient makes in order to receive a diagnosis. The average rare disease patient often waits months to years for a diagnosis and is misdiagnosed multiple times. The financial devastation for a patient on this journey is often extraordinary and the prolonged time spent searching for a diagnosis has a negative impact on an individual’s ability to stay employed and maintain insurance coverage. At the end of this odyssey, the relief of finally getting an answer is quickly replaced by the painful fact that only about 300 of the 7,000 rare diseases have any sort of an effective treatment.

Because society has not found cures or effective treatments for even 5% of rare diseases, our community depends on social safety nets for our survival. While many Americans think of Medicaid as primarily a program for low-income families, Medicaid is also a lifeline for the disabled community made up of people who face a lifetime of chronic illness. For those of us with impaired children and full time jobs, Medicaid subsidizes our private insurance with specialized care so that we can go to work and remain taxpayers. Medicaid is the difference between putting our children in a nursing home (a far more expensive option in the long run) or having them home with their siblings and parents. For working adults with a rare condition, Medicaid is the assurance that if our disease increases in severity – as it does at unpredictable times – we won’t go without vital medical care between losing one job and finding another. Medicaid is the knowledge for those of us who are caregivers for our disabled adult children that when we can longer work and provide private insurance coverage our children will still be cared for.

Our rare disease community is vast and diverse. Rare diseases do not discriminate between race, socioeconomic status, or geographical region. We hear people casually repeat caricatures of Medicaid recipients and we wince at the oversimplifications. When we listen to the debates raging around us regarding the future of Medicaid we simply ask you to look past the stereotypes and consider the very real consequences Medicaid cuts will have on real people in your community living with rare diseases.

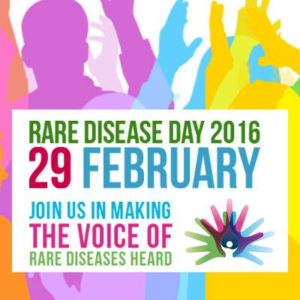

February 28th is internationally recognized as Rare Disease Day. My daughter, Chloe, was diagnosed with a rare and terminal disease at the age of two in a miraculously short time due to the brilliance of her neurologist. The neurologist was Canadian. Chloe’s only hope of survival was a bone marrow transplant, a risky and arduous procedure. We put our youngest child’s life in the hands of a capable and caring surgeon at the Mayo Clinic. She was Pakistani. Throughout the transplant there were long days of agony and fear as we awaited the outcome. Since her immune system was completely gone, neither she nor I could leave our tiny ICU room. The resident on the medical team brought me a Starbucks coffee each morning. He was Egyptian. When it became clear that Chloe’s chances for survival were non-existent, we met with the team to decide whether to try a risky and painful second transplant or let her go. I shared with the doctors that I believed deeply in medicine but also that, at the end of the day, my Christian faith informed me that it is God who decides how many days we have on this earth. I sensed that my decision resonated deeply with my Pakistani doctor’s faith as well. She was a Muslim.

February 28th is internationally recognized as Rare Disease Day. My daughter, Chloe, was diagnosed with a rare and terminal disease at the age of two in a miraculously short time due to the brilliance of her neurologist. The neurologist was Canadian. Chloe’s only hope of survival was a bone marrow transplant, a risky and arduous procedure. We put our youngest child’s life in the hands of a capable and caring surgeon at the Mayo Clinic. She was Pakistani. Throughout the transplant there were long days of agony and fear as we awaited the outcome. Since her immune system was completely gone, neither she nor I could leave our tiny ICU room. The resident on the medical team brought me a Starbucks coffee each morning. He was Egyptian. When it became clear that Chloe’s chances for survival were non-existent, we met with the team to decide whether to try a risky and painful second transplant or let her go. I shared with the doctors that I believed deeply in medicine but also that, at the end of the day, my Christian faith informed me that it is God who decides how many days we have on this earth. I sensed that my decision resonated deeply with my Pakistani doctor’s faith as well. She was a Muslim.

Driving home from work last week it was surreal to listen to local news coverage of the live press conference in Chanhassen, MN, knowing that the whole world was tuning in to my home town. Local law enforcement was addressing the public outside of Paisley Park, home of the rock legend Prince who, of course, had just died. The grief for us Minnesotans is unique and multilayered because Prince, while being an intensely private man, was also deeply embedded in his Minneapolis community and its suburbs where he was born and raised. After the renovation of the Minneapolis fixture the Uptown Theater, a local movie critic mentioned in passing that Prince occasionally slipped in to watch a film. (It became my habit after that to scan the audience to see if he and I had the same cinematic taste.) He had his own private table at the Dakota Jazz Club downtown. Some of my friends live a few doors down from one of his rental properties. I had even heard that he would once in a while do some door to door evangelizing for his small church located in St. Louis Park just minutes from my own home.

Driving home from work last week it was surreal to listen to local news coverage of the live press conference in Chanhassen, MN, knowing that the whole world was tuning in to my home town. Local law enforcement was addressing the public outside of Paisley Park, home of the rock legend Prince who, of course, had just died. The grief for us Minnesotans is unique and multilayered because Prince, while being an intensely private man, was also deeply embedded in his Minneapolis community and its suburbs where he was born and raised. After the renovation of the Minneapolis fixture the Uptown Theater, a local movie critic mentioned in passing that Prince occasionally slipped in to watch a film. (It became my habit after that to scan the audience to see if he and I had the same cinematic taste.) He had his own private table at the Dakota Jazz Club downtown. Some of my friends live a few doors down from one of his rental properties. I had even heard that he would once in a while do some door to door evangelizing for his small church located in St. Louis Park just minutes from my own home. Before my daughter passed away from a rare disease I had never heard of “Rare Disease Day” and knew next to nothing about the impact rare disorders have on society. Over the past few years I have learned that rare diseases play a larger role in public health than most people realize and deserve consideration from the medical community, policy makers, and the general public.

Before my daughter passed away from a rare disease I had never heard of “Rare Disease Day” and knew next to nothing about the impact rare disorders have on society. Over the past few years I have learned that rare diseases play a larger role in public health than most people realize and deserve consideration from the medical community, policy makers, and the general public.

Join us at a State House Reception as we make the voice of rare diseases heard in Minnesota! This session, state legislators will be voting on a bill to create the Chloe Barnes Rare Disease Advisory Council. The council gives the rare disease community a direct voice to our lawmakers. This year’s reception will feature patient advocates, researchers, and legislators who will talk about the issues that the advisory council will address

Join us at a State House Reception as we make the voice of rare diseases heard in Minnesota! This session, state legislators will be voting on a bill to create the Chloe Barnes Rare Disease Advisory Council. The council gives the rare disease community a direct voice to our lawmakers. This year’s reception will feature patient advocates, researchers, and legislators who will talk about the issues that the advisory council will address

This week the story of Turing Pharmaceutical CEO Martin Shkreli and his hiking of the price of a decades-old pill that treats the serious illness toxoplasmosis from $13.50 to $750 broke. I was outraged as the vast majority of Americans were. But a special wave of nausea swept over me when I read more about this former hedge-fund manager turned biotech venture capitalist. In his biography, characterized by an incessant thirst for wealth and shady business practices, is a fact of personal significance to me. In 2011, Mr. Shkreli founded biotech firm Retrophin with the goal of focusing on medicines for rare diseases.

This week the story of Turing Pharmaceutical CEO Martin Shkreli and his hiking of the price of a decades-old pill that treats the serious illness toxoplasmosis from $13.50 to $750 broke. I was outraged as the vast majority of Americans were. But a special wave of nausea swept over me when I read more about this former hedge-fund manager turned biotech venture capitalist. In his biography, characterized by an incessant thirst for wealth and shady business practices, is a fact of personal significance to me. In 2011, Mr. Shkreli founded biotech firm Retrophin with the goal of focusing on medicines for rare diseases.